Evolutionary Archaeology

Beginning in the late 1960s, some archaeologists have (again) turned towards Darwinian Theory as an underlying explanatory framework for explaining the phenomena observed in the archaeological record (Clarke 1968; Dunnell 1971, 1978, 1980). Evolutionary Archaeology labels a heterogeneous assortment of approaches unified by its reference to Darwin’s theory of ‘descent with modification’ (Kuhn 2004; Maschner 1996; Teltser 1995). The conceptual premise for an Evolutionary Archaeology is that because any system in which the accurate (or near-accurate) transmission of generation leads to trans-generational state changes in its participants (Jablonka and Lamb 2006; Lewontin 1970), human culture can be modelled in Darwinian terms. As such it stands in contrast to schools of ‘cultural evolutionism’ based on the work of the anthropologists Tylor, Morgan and White, which despite being steeped in evolutionary terminology, do not in fact consider human culture as following Darwinian lines (Dunnell 1980, 1988).

While anthropologists and archaeologists have intermittently taken inspiration from evolutionary theory since the inception of the discipline (Riede 2006b), explicitly evolutionary archaeological approaches have rises to greater prominence only in the last ten years. They are primarily aimed at explaining comparatively large-scale material cultural and behavioural changes over time as documented in the archaeological record. Drawing extensively on the theory and methods used in evolutionary biology, Evolutionary Archaeology has a strong quantitative orientation. In particular, phylogenetic techniques, used in biology to study the evolutionary relationships of populations, species, genera, etc. have come to play an important role at reconstructing “intellectual lineages” (Harmon et al. 2006: 209) reflected in the material culture of the archaeological record (Borgerhoff-Mulder 2001; Collard, Shennan and Tehrani 2006; Lipo et al. 2006; Mace, Holden and Shennan 2005; O’Brien et al. 2003).

Introduction

Evolutionary Archaeology (EA) is here taken to refer to a heterogeneous set of archaeological theories and practices unified through their reference to Darwinism. More specifically, it refers to the approach that is founded on dual-inheritance theory (Boyd and Richerson 1985; Richerson and Boyd 2005) in which culture is treated as a system of information transmission following Darwinian rules parallel to and (in the first instance) independent from genetic transmission. It is not to be mistaken with the cultural evolutionism founded by Morgan, Taylor and Spencer, which represents an often confounded body of theory (see Dunnell 1980 and Leonard 2001 for discussions of this issue). This contribution will briefly review the seeds of evolutionary approaches to material culture changes found in the writing of the pioneers of academic archaeology, especially in Scandinavia (see also Riede 2006b). As far back as 1873, references to Darwin’s theory of ‘descent with modification’ became common in Swedish archaeology. Significantly, it was in Scandinavia that archaeology began as an independent academic discipline (Daniel 1981; Klindt-Jensen 1975; Trigger 1989) and it was some of the very same pioneer archaeologists who also saw themselves as material culture Darwinists.

Through the political and social upheavals of the 20th century, this approach lost much of its impetus, despite a number of revival attempts (e.g., Clarke 1968; Cullen 1993, 1995, 1996b, a). Many archaeologists today pursue alternative research agendas (see Hodder 2001) that very rarely incorporate considerations of how cross-generational descent with modification in social information transmission shapes the archaeological record. In contrast, the culture historians of the 19th century were primarily interested in long-term artefactual change and demography, and contemporary EA shares many interests and goals with traditional culture history (see Anthony 1990; Härke 1998; Lyman and O’Brien 1998; O’Brien and Lyman 1999, 2000b, 2002; Rosenberg 1994; Shennan 2000, 2002, 2004; Tschauner 1994).

‘Evolution’ is doubtlessly one of archaeology’s most used – and perhaps most abused – words. However, evolution comes in many guises and it is only really in the last 30 years that an explicitly Darwinian approach has emerged in archaeology (Leonard 2001; O’Brien 1996; Shennan 2002). At present, the number of publications in EA is rising almost exponentially, reflecting in part a wider trend of applying evolutionary models to human behaviour (e.g., Barrett, Dunbar and Lycett 2002; Laland and Brown 2002; Mesoudi 2007; Mesoudi, Whiten and Laland 2004; Mesoudi, Whiten and Laland 2006; O’Brien in press; Shennan 2002, in press; Wells, Strickland and Laland 2006; see also www.ceacb.ucl.ac.uk/resources and www.kli.ac.at/theorylab for comprehensive listings).

Scientific Archaeology, Its Task, Requirements and Rights

‘Scientific Archaeology, Its Task, Requirements and Rights’ is the title of a pamphlet published by the Swedish numismatist and archaeologist Hans Hildebrand (1842–1913) in 1873 (Hildebrandt 1873). In this pamphlet he outlined the state-of-the-art of archaeology at the time (Hildebrandt 1873: 16):

One might call the new stage which archaeology has entered ‘the typological stage’. Our next task is to establish the types, to ascertain which of them are characteristic of each region, to search out the types’ affinities, and to unfold their history; and the type to be investigated in this sense is both the finished instrument and the smallest ornament which adorns it…The many similar objects are only ostensibly duplicates, the many axes…do not have the same importance as number of specimens of an animal species in a zoological museum. Slight differences appear in these axe specimens, and thus they do not in general correspond to specimens of animals but to species and varieties; here, the formation of varieties is greater on account of man’s influence on developments…Under the influence of two factors – the practical need and the craftsman’s taste – a great many forms arise, each of which has to struggle for its existence; one does not find what it needs for its existence and succumbs, but the other moves forward and produces a whole series of forms.

The allusions to Darwin’s theory of descent with modification, first published in 1859 in English (Darwin 1998[1859]), are evident. Darwin’s ideas were widely discussed in intellectual circles all across Europe and this included archaeologists in Denmark and Sweden (see Schoch 1997; Stott 2003; Fischer 2002; www.lib.cam.ac.uk/Departments/Darwin). Interestingly however, the number of references to Darwin’s work increased sharply just after the translation of The Origin of Species and The Descent of Man into Swedish and Danish (Darwin 1871, 1872b, a, 1874) in 1871 and 1872 and 1872 and 1874 respectively. In effect, Hildebrand proposed that although there are necessary differences between the biological and the cultural domain of evolution, the structural similarities between the two subjects warrant the application of Darwinian reasoning to both (Hildebrandt 1880). He was succeeded by Gustaf Oscar Augustin Montelius (1843–1921) who is widely considered to be the father of the so-called ‘typological method’ (Gräslund 1999). He was committed to solving archaeology’s rapidly increasing chronological challenges and in this endeavour codified the ‘typological method’ of identifying cultural similarity and dissimilarity. His papers contain explicit references to Darwinian evolutionary theory as early as 1884 (see Riede 2006b; Figure 1). In 1903, Montelius published what might be seen as the first stand-alone handbook of archaeological method and theory. In this he asserts (Montelius 1903: 20):

It is an actual fact rather amazing that Man in his labours has been and is subject to the very same laws of evolution. Is human freedom indeed so limited as to deny him the creation of any desired form? Are we forced to go, step by step, from one form to the next, be they ever so similar? Prior to studying these circumstances in depth, one can be tempted to answer such question with «no». However, since one has investigated human labours rather more closely, one finds that clearly, the answer has to be «yes». This evolution can be slow or fast, but at all times Man, in his creation of new forms, needs to conform to the very same principles that hold sway over the rest of nature.

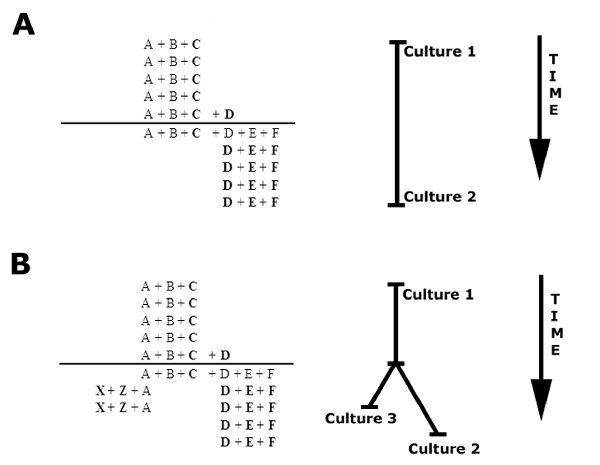

Figure 1. (A) The formal series of letters is taken from Montelius (1903) where it was presented to demonstrate the ‘find-combination method’ and the archaeological definition of cultures. From this series it is clear that Culture 1 is different from Culture 2, but that both share certain characteristics at the extreme ends of their distribution. Such a scheme corresponds to anagenetic evolution. (B) When Montelius’ scheme is expanded to include a second derived culture, such as Culture 3, cladogenetic evolution ensues (see the extended discussion of phylogenetics below). The line dividing Culture 1 from Culture 2 in A and from Cultures 2 and 3 in scenario B may correspond to an event documented in stratigraphic sequences, but can also be internal to a given society. Montelius’ thinking was in line with that of Darwin. See Hennig (1966) and Sober (1993) for the principles of cladogenetic evolution.

It can so be argued that the notion of social information transmission between generations was central to the work of culture historians, both in Europe as well as in North America (Lyman and O’Brien 1997, 2000a, 2003; Lyman and O’Brien 2004; Lyman, O’Brien and Dunnell 1997a, b; Lyman, Wolverton and O’Brien 1998; O’Brien and Lyman 1999, 2000b). The end of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century saw a strong decline in the popularity of Darwinism both amongst professional biologists as well as the general public (e.g., Bowler 1983, 1993, 2003; Nordenskiöld 1926; see also Huxley’s (1943: 22) “eclipse of Darwinism”). The increasing rift between archaeology and Darwinian Theory during this time may have its roots in the increasing specialisation of academia, the misuse of (pseudo-) Darwinian rhetoric for racist policies in the run-up to WW I and II, as well as in the move away of biology from palaeontology towards genetics. It is interesting to note, for instance, that it took biologists many decades to rid themselves of the stifling typological thinking (Hull 1965; Mayr 1957), a conceptual development that has no parallel in archaeology as a whole (Lyman and O’Brien 2003; Lyman and O’Brien 2004; O’Brien and Lyman 2004).

In addition, however, dormant theoretical issues – especially the conflation of emic and etic units of analysis, and the mechanisms of transmission of cultural information – led culture historical archaeologists into an intellectual quagmire (Lyman et al. 1997b) and resulted in such outcries against evolutionary approaches to cultural evolution as Brew’s (1943: 53) statement that “phylogenetic relationships do not exist between inanimate objects”. With many basic chronologies seemingly worked out, new generations of archaeologists were eager to explore alternative avenues of research. The 1960s and 1970s saw an institutional backlash against the culture historical school, predicated largely on strong rhetoric rather than substantive criticisms (O’Brien, Lyman and Schiffer 2005; Shennan 2002; Trigger 1989). So-called Processualism, primarily concerned with synchronic and taphonomic questions (see Lyman 2007) rose to dominance in archaeology, but to many it is now clear that it could not live up to its great promise. One of the founding father of modern EA, Robert Dunnell (1995: 33) put it most succinctly: “In retrospect, one of the most serious flaws in processual archaeology was its failure to rethink its language of observation, its systematics”. Dunnell has been one of processualism’s most persistent critics and he was one of the first archaeologists to look, once more, in earnest at the structural and conceptual similarities between archaeology and evolutionary biology, especially palaeobiology. In a series of papers he has clarified many of the critical shortcomings of traditional culture history and outlined an archaeological theory of diachronic culture change that hinges on systematics and Darwinian Theory (Dunnell 1971, 1978a, b, 1980, 1982, 1986, 1988, 1989, 1992, 1995).

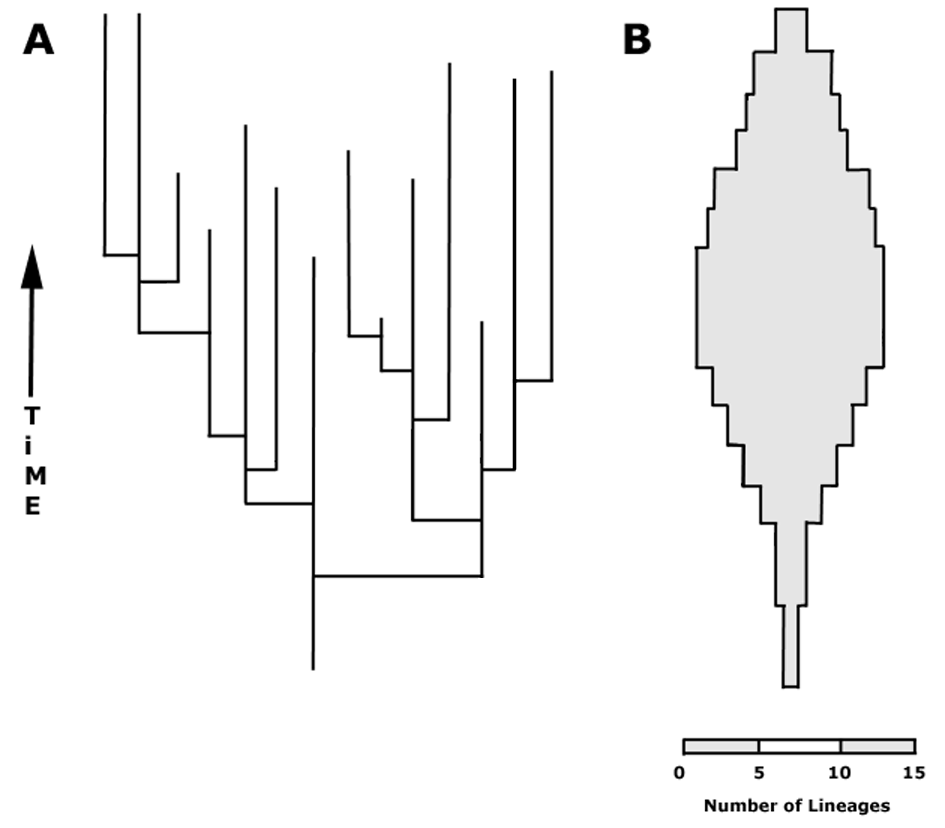

EA today explicitly addresses issues of systematics, i.e. of how meaningful or appropriate units of socially transmitted cultural information – perhaps a pragmatic and empirically derived material culture analogue to memes (Dawkins 1976) or “cultural DNA” (Distin 2005: 36) – can be identified (Leonard and Jones 1987; O’Brien and Lyman 2000b; Ramenofsky and Steffen 1998; Tschauner 1994). In contrast to Memetics, however, EA is relatively unconcerned with identifying the neurological counterpart to the gene (i.e., memes; see, for instance, Aunger 2002; Blackmore 1999) because a) those traits consistently transmitted in chains of teaching and learning can be identified through detailed material culture studies (O’Brien, Darwent and Lyman 2001; Riede 2006a) and because b) particulate units of cultural inheritance are not in fact necessary for culture to be treated as an evolutionary phenomenon (Boyd and Richerson 2000; Henrich and Boyd 2002). Seriation, one of the method originally used by culture historians to study cultural continuity and discontinuity in material culture, is now recognised as identical to ‘collapsed’ so-called clade-diversity diagrams – one tracking anagenetic the other cladogenetic evolution (Figure 2; Lyman and O’Brien 2000b, 2006). This similarity has prompted the application of phylogenetic methods to archaeological material (O’Brien and Lyman 2000a, 2002, 2003; O’Brien et al. 2003; O’Brien et al. 2002) in order to track the “replicative success” (Leonard and Jones 1987: 212) of particular variants through successive cladogenetic events.

In brief, phylogenetics is the summary term for a broad range of approaches that attempt to reconstruct and thus understand evolutionary pathways through branching diagrams. The sequence of branching displayed is the result of increasingly exclusive sharing of particular character states amongst the units (or taxa) considered in any given analysis. This approach was pioneered by the entomologist Willi Hennig (Hennig 1965, 1966) and quickly revolutionised the study of evolutionary biology (Gee 2000; Ridley 1986). It is important to note that in cladistics it is not overall similarity that determines evolutionary proximity, but the presence or absence of suites of shared character states. Phylogenetic analyses and their output – phylogenies – must be seen as hypotheses of historical relatedness, which can then be tested against evidence external to the data on which the phylogenies themselves are built, such as stratigraphic sequence or radiocarbon dating (Felsenstein 2004; O’Brien et al. 2003; Skelton, Smith and Monks 2002). Interestingly, similar analytical methods were developed independently by comparative linguists and stemmatists (Hoenigswald and Wiener 1987; Platnick and Cameron 1977), lending additional support to the claim that the phylogenetic method holds validity beyond the biological realm. To-date a wide range of software applications are available, many of which are free of charge (see http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip/software.html for a comprehensive listing).

Figure 2. A cladogram (A) and a seriation or clade-diversity diagram (B). The latter measures total taxonomic diversity over time while the former measures both diversity as well as relatedness amongst taxonomic units. Redrawn from Lyman et al. (1998: 248).

Complementary ethnographic studies provide data on how different means of information transmission ‘on the ground’ may shape the phylogenetic pathways of such traits, the mode and tempo of their evolution (Table 1). On occasion scenarios of craft skill teaching and learning can be identified in the archaeological record (e.g., Bodu, Karlin and Ploux 1990; Finlay 1997; Fischer 1989, 1990; Högberg 1999; Milne 2005; Pigeot 1990) and such instances (of exceptional archaeological preservation) can be used to explicitly and empirically link the dynamics of information transmission in rich social contexts to the long-term technological and stylistic changes recorded in the archaeological record.

| Modes of Cultural Transmission | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | Vertical | Horizontal | One to Many | Many to One |

| Transmitter | Parents | Unrelated | Teachers, “masters” | Elders, “masters” |

| Learner | Child | Unrelated | Pupils, “apprentices” | Youths, “apprentices” |

| Acceptance of innovation | Moderately difficult | Easy | Easy | Very difficult |

| Cultural variation between actors | High | Can be high | Low | Low |

| Cultural variation between groups | High | Can be high | Can be high | Small |

| Tempo of cultural evolution | Slow | Can be rapid | Can be rapid | Slow |

Table 1. In contrast to the gamut of genetic transmission (but see Jablonka and Lamb 2005), cultural transmission can follow non-vertical pathways. However, ethnographic studies of traditional societies have shown that for many craft skills – which in turn would precipitate in the archaeological record – vertical transmission dominates (Guglielmino et al. 1995; Hewlett and Cavalli-Sforza 1986; Hewlett, de Silvestri and Guglielmino 2002; Shennan 1996; Shennan and Steele 1999). Consistent vertical transmission over long time scales would produce similar patterns in cultural and biological phylogenies (Foley 1987), but for cultural phylogenetics itself to be warranted the important feature of information transmission would be from parent to offspring generation. Adapted from MacDonald (1998).

Evolutionary Archaeology Today

In principle, Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species (Darwin 1998[1859]) has equipped human scientists with a complete framework for the evolutionary study of “the diverse range of beliefs, knowledge, and artifacts that constitute human culture” (Mesoudi et al. 2004: 1). To-date, EA is one of many theoretical schools within the discipline of archaeology (Leonard 2001), and it is situated within the wider trend of the application of Darwinian principles to human behaviour (Laland and Brown 2002). Smith has recently argued that three distinct, yet related ‘styles’ of evolutionary explanation have been brought to bear on past human behaviour as reflected in the archaeological record (Smith 2001; Table 2). While EA does draw on insights from evolutionary psychology as well as behavioural ecology, there is considerable disagreement over the degree to which these different Darwin-inspired approaches are compatible (Boone and Smith 1998; Kuhn 2004; O’Brien, Lyman and Leonard 1998). EA – in contrast to the other ‘styles’ – is founded on the reformulation of culture as a system of information transmission with sufficient and necessary formal similarities to biological information transmission to warrant the application of Darwinian principles (Jablonka and Lamb 2006; Shennan 1989, 2005, 2006). This then is Darwinian evolution in an abstract sense rather than a simple widening of the scope of biological evolution. Such an extension of Darwinian reasoning to non-genetic inheritance systems is rapidly becoming accepted (e.g., Forster and Renfrew 2006; Jablonka and Lamb 2005; Odling-Smee, Laland and Feldman 2003; Wells et al. 2006). Most recently, Jablonka and Lamb (2006: 237; added emphasis) note that…

… the transmission of information between generations, whether through reproduction or through communication, requires that a receiver interprets (or processes) an informational input from a sender who was previously a receiver. When the processing by the receiver leads to the reconstruction of the same or a slightly modified organization-state as that in the sender, and when variations in the sender’s state lead to similar variations in the receiver, we can talk about the hereditary transmission of information. This typically occurs through reproduction, but it can also occur through communication if communication leads to a trait of one individual being reconstructed in another . Clearly, if the hereditary transmission of information is seen in this way, there is no need to assume that all hereditary variations and all evolution depend on DNA changes.

Backed by the development and application of a battery of “exciting new methods” (Borgerhoff-Mulder, Nunn and Towner 2006: 53), many of whom are adapted from palaeontology and population genetics, EA has become a vibrant research programme with, by now, its own textbooks (e.g., O’Brien and Lyman 2000b; O’Brien et al. 2003; Shennan 2002) and technical vocabulary (Hart and Terrell 2002; see also O’Brien et al. 2003 and Borgerhoff-Mulder et al. 2006 for glossaries) and an increasing number of worked-through case studies (see the edited volumes of Collard, Shennan and Tehrani 2006; Mace, Holden and Shennan 2005, Lipo et al. 2006, O’Brien in press and Collard et al. 2006; Shennan in press).

| Evolutionary Psychology | Behavioural Ecology | Dual-Inheritance Theory | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is being explained? | Psychological mechanisms | Behavioural strategies | Cultural evolution |

| Key constraints | Cognitive, genetic | Ecological, material | Structural, information |

| Temporal scale of adaptive change | Long-term (genetic) | Short-term (phenotypic) | Medium-term (cultural) |

| Expected current adaptedness | Lowest | Highest | Intermediate |

| Hypothesis generation | Informal inference | Optimality models | Population-level models |

| Hypothesis-testing methods | Survey, lab experiment | Quantitative ethnographic observation | Mathematical modelling and simulation |

| Favoured topics | Mating, parenting, sex differences | Subsistence, reproductive strategies | Large-scale cooperation, mal-adaptation |

Table 2. The three styles of Darwinian explanation employed in the study of human behaviour. Each of these approaches has been applied to specifically archaeological case studies (see Shennan 2002).

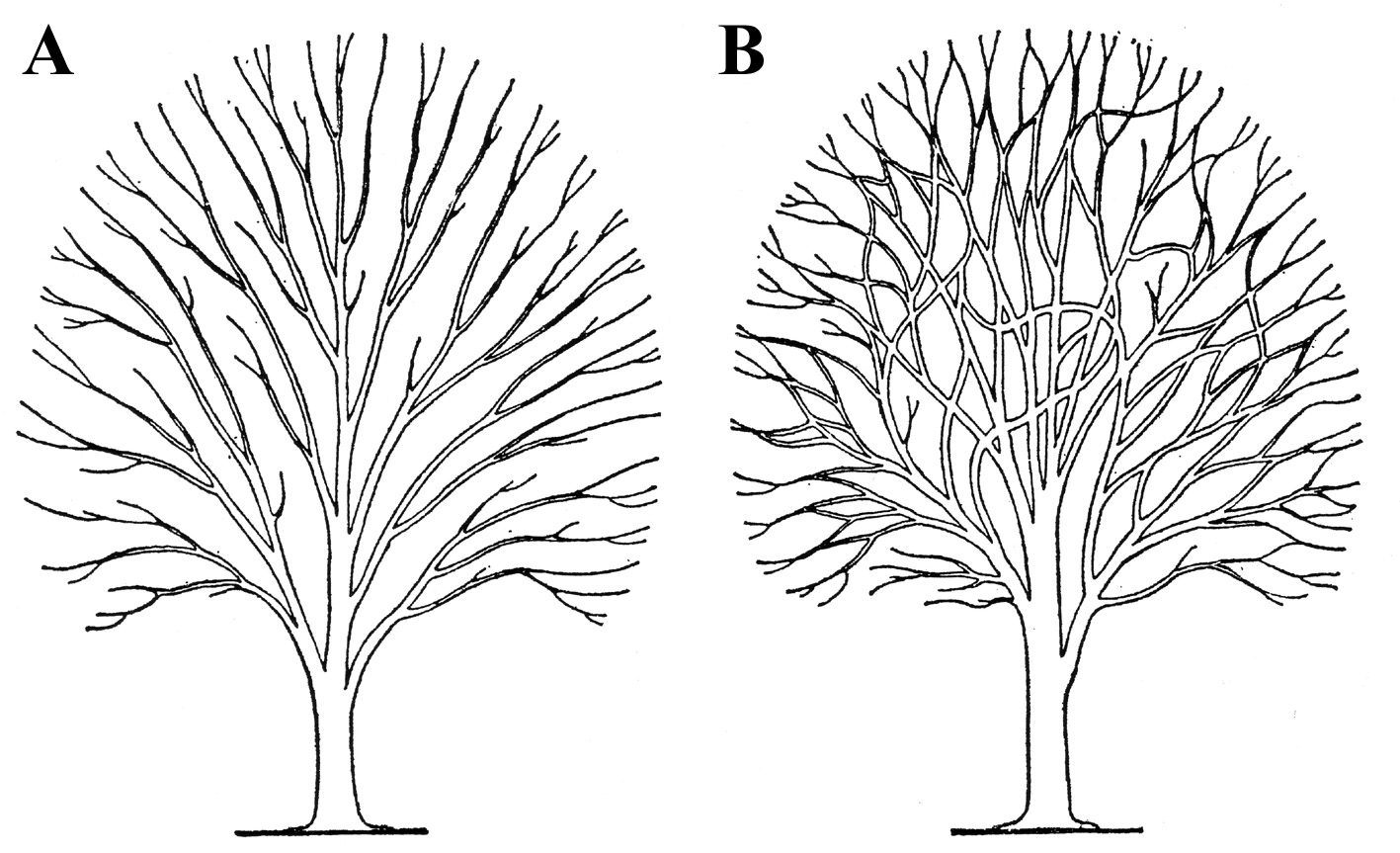

Many of the concerns and research topics of EA are close to those discussed in the early days of anthropological and archaeological inquiry, such as human demography, migration and changes in the styles and fashions of material culture. This return to such old staples does not, however, indicate that contemporary Darwinian archaeologists align themselves with scholars such as Tylor and Morgan and the kinds of pre-Darwinian progressive, teleological and deterministic evolutionary schemes made fashionable by them in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Instead, it reflects the fact that these issues were and indeed are important ones fundamental to anthropology and archaeology then and now. Using an evolutionary approach to cultural diversity and employing phylogenetic methods similar to those used in biology, it has recently been shown empirically that “branching cannot be discounted as a process in cultural evolution” (Collard et al. 2006: 180). Past concerns that blending or reticulating evolution distorts the phylogenetic patterns in cultural evolution (Figure 3) can now be subjected to empirical investigation. A number of methods have been developed that allow reticulation to be incorporated into cultural phylogenetic analysis (e.g., Bryant, Filimon and Gray 2005; Croes, Kelly and Collard 2005; Forster and Toth 2003; Riede 2007a, b) and Cronk (2006: 195) has argued that “the phylogenetic method should be placed alongside cultural transmission theory, geneculture coevolution, signaling theory, experimental economic games, niche construction, and animal culture studies in our toolkit for studying culture from an evolutionary perspective”.

Figure 3. A perfectly resolved tree (A) and a tree in which blending/reticulation has obscured some of the phylogenetic relationships (B). Prior to the development of robust phylogenetic theory and the wide-spread availability of powerful computational methods many archaeologists and anthropologists shied away from applying phylogenetic principles to material culture data. Adapted from Clarke (1968: 147).

Although it is not clear whether a unified Darwinian paradigm for the study of human evolution, behaviour and culture is possible or even desirable (Ingold 2000, 2007; Maschner 1996; Mesoudi et al. 2006; Mesoudi, Whiten and Laland 2007), such an approach would certainly incorporate the methods developed and insights gained by evolutionary archaeologists over the last 130 years (Figure 4; Mesoudi et al. 2006).

Figure 4. The major subdivisions in the study of biotic and cultural evolution as presented by Mesoudi et al. (2006) and the place of EA amongst other styles of evolutionary analysis of human behaviour and culture.

Bibliography

Anthony, D.W. (1990). “Migration in Archaeology: The Baby and the Bathwater”. American Anthropologist, 92: 895-914.

Aunger, R. (2002). “The Electric Meme. A New Theory of How We Think”. New York: Free Press.

Barrett, L., R. Dunbar and J. Lycett (2002). “Human Evolutionary Psychology”. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Blackmore, S. (1999). “The Meme Machine”. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bodu, P., C. Karlin and S. Ploux (1990). “Who’s who? The Magdalenian flintknappers of Pincevent, France”. In Cziesla, E., S. Eickhoff, N. Arts and D. Winter, eds., The Big Puzzle: International Symposium on Refitting Stone Artefacts, Monrepos, 1987. Bonn: Holos.(143-63)

Boone, J.L. and E.A. Smith (1998). “Is It Evolution Yet? A Critique of Evolutionary Archaeology”. Current Anthropology,39: S141-S73.

Borgerhoff-Mulder, M. (2001). “Using Phylogenetically Based Comparative Methods in Anthropology: More Questions Than Answers”. Evolutionary Anthropology, 10: 99-110.

Borgerhoff-Mulder, M., C.L. Nunn and M.C. Towner (2006). “Cultural Macroevolution and the Transmission of Traits”. Evolutionary Anthropology, 15: 52-64.

Bowler, P.J. (1983). “The Eclipse of Darwinism: anti-Darwinian evolution theories in the decades around 1900”. Baltimore, MA.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bowler, P.J. (1993). “Biology and social thought, 1850-1914”. Berkeley, CA.: Office for History of Science and Technology.

Bowler, P.J. (2003). “Evolution: The History of an Idea”. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

Boyd, R. and P.J. Richerson (1985). “Culture and the evolutionary process”. Chicago, IL.: University of Chicago Press.

Boyd, R. and P.J. Richerson (2000). “Memes: Universal Acid or a Better Mouse Trap”. In Aunger, R., ed. Darwinizing Culture: The Status of Memetics as a Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.(143-62)

Brew, J.O. (1943). “Archaeology of the Alkali Ridge, Southeastern Utah. With a Review of the Mesa Verde Division of the San Juan and Some Observations on Archaeological Systematics”. Cambridge, MA.: Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology.

Bryant, D., F. Filimon and R.D. Gray (2005). “Untangling our Past: Languages, Trees, Splits and Networks”. In Mace, R., C.J. Holden and S.J. Shennan, eds., The Evolution of Cultural Diversity. A Phylogenetic Approach. London: UCL Press.(67-83)

Clarke, D.L. (1968). “Analytical Archaeology”. London: Methuen & Co.

Collard, M., S.J. Shennan and J.J. Tehrani (2006). “Branching, blending, and the evolution of cultural similarities and differences among human populations”. Evolution and Human Behaviour, 27: 169-84.

Croes, D., K.M. Kelly and M. Collard (2005). “Cultural historical context of Qwu?gwes (Puget Sound, USA): a preliminary investigation”. Journal of Wetland Archaeology, 5: 141-54.

Cronk, L. (2006). “Bundles of Insights About Culture, Demography, and Anthropology”. Evolutionary Anthropology, 15: 196-99.

Cullen, B.S. (1993). “The Darwinian Resurgence and the Cultural Virus Critique”. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 3: 179-202.

Cullen, B.S. (1995). “Living artefact, personal ecosystem, biocultural schizophrenia: a novel synthesis of processual and post-processual thinking”. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 61: 371-91.

Cullen, B.S. (1996a). “Social interaction and viral phenomena”. In Steele, J. and S.J. Shennan, eds., The Archaeology of Human Ancestry. Power, Sex and Tradition. London: Routledge.(420-33)

Cullen, B.S. (1996b). “Cultural Virus Theory and the Eusocial Pottery Assemblage”. In Maschner, H.D.G., ed. Darwinian Archaeologies. New York, N.Y.: Plenum.(43-59)

Daniel, G.E. (1981). “A Short History of Archaelolgy”. London: Thames & Hudson.

Darwin, C. (1871). “Om arternas uppkomst genom naturligt urval eller de bäst utrustade rasernas bestånd i kampen för tillvaron”. Stockholm: L. J. Hierta.

Darwin, C. (1872a). “Om Artenes Oprindelse ved Kvalitetsvalg eller ved De Heldigst Stillede Formers Sejr i Kampen for Tilværelsen. Oversat af J.P. Jacobsen”. København: Gyldendalske Boghandel.

Darwin, C. (1872b). “Menniskans härledning och könsurvalet”. Stockholm: Bonnier.

Darwin, C. (1874). “Menneskets Oprindelse og Parringsvalget. Paa Dansk ved J.P. Jacobsen”. København: Gyldendalske Boghandel.

Darwin, C. (1998[1859]). “The Origin of Species”. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, R. (1976). “The Selfish Gene”. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Distin, K. (2005). “The Selfish Meme. A Critical Reassessment”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dunnell, R.C. (1971). “Systematics in Prehistory”. New York, N.Y.: Free Press.

Dunnell, R.C. (1978a). “Archaeological potential of anthropological and scientific models of function”. In Dunnell, R.C. and E.S. Hall, eds., Archaeological essays in honour of Irving B. Rouse. The Hague: Mouton Publishers.(41-73)

Dunnell, R.C. (1978b). “Style and Function: A Fundamental Dichotomy”. American Antiquity, 43: 192-202.

Dunnell, R.C. (1980). “Evolutionary Theory in Archaeology”. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, 3: 35-99.

Dunnell, R.C. (1982). “Science, Social Science, and Common Sense: The Agonizing Dilemma of Modern Archaeology”. Journal of Anthropological Research 38: 1-25.

Dunnell, R.C. (1986). “Methodological Issues in Americanist Artifact Classification”. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, 9: 149-207.

Dunnell, R.C. (1988). “The Concept of Progress in Cultural Evolution”. In Nitecki, M.H., ed. Evolutionary Progress. Chicago, IL.: University of Chicago Press.(169-94)

Dunnell, R.C. (1989). “Aspects of the application of evolutionary theory in archaeology”. In Lamberg-Karlowski, C.C., ed. Archaeological Thought in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.(34-49)

Dunnell, R.C. (1992). “Is a Scientific Archaeology Possible?” In Embree, L., ed. Metaarchaeology: Reflections by Archaeologists and Philosophers. London: Kluwer Academic.(75-91)

Dunnell, R.C. (1995). “What Is It That Actually Evolves?” In Teltser, P.A., ed. Evolutionary Archaeology: Methodological Issues. Tucson, AZ.: The University of Arizona Press.(33-50)

Felsenstein, J. (2004). “Inferring Phylogenies”. Sunderland, MA.: Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Finlay, N. (1997). “Kid knapping: the missing children in lithic analysis”. In Moore, J. and E. Scott, eds., Invisible People and Processes: Writing Gender and Childhood into European Archaeology. Leicester: Leicester University Press.(203-13)

Fischer, A. (1989). “A Late Palaeolithic “School” of Flint-Knapping at Trollesgave, Denmark. Results from Refitting”. Acta Archaeologica, 60: 33-49.

Fischer, A. (1990). “On Being a Pupil of a Flintknapper of 11,000 Years Ago. A preliminary analysis of settlement organization and flint technology based on conjoined flint artefacts from the Trollesgave site”. In Cziesla, E., S. Eickhoff, N. Arts and D. Winter, eds., The Big Puzzle: International Symposium on Refitting Stone Artefacts, Monrepos, 1987. Bonn: Holos.(447-64)

Fischer, A. (2002). “Introduction to Chapter 5: Steenstrup 1859”. In Fischer, A. and K. Kristiansen, eds., The Neolithistion of Denmark. 150 Years of Debate. Sheffield: J.P. Collins Publications.(58)

Foley, R.A. (1987). “Hominid species and stone tools assemblages: how are they related?” Antiquity, 61: 380-92.

Forster, P. and A. Toth (2003). “Toward a phylogenetic chronology of ancient Gaulish, Celtic, and Indo-European”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100: 9079-84.

Forster, P. and C. Renfrew, eds. (2006). “Phylogenetic Methods and the Prehistory of Languages”. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs.

Gee, H. (2000). “Deep Time: Cladistics, the Revolution in Evolution”. London: Fourth Estate.

Gräslund, B. (1999). “Gustaf Oscar Augustin Montelius 1843-1921”. In Murray, T., ed. Encyclopaedia of archaeology. The great archaeologists. Oxford: ABC-Clio.(155-63)

Guglielmino, C.R., C. Viganotti, B. Hewlett and L.L. Cavalli-Sforza (1995). “Cultural variation in Africa: Role of mechanisms of transmission and adaptation”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 92: 7585-89.

Harmon, M.J., T.L. VanPool, R.D. Leonard, C.S. VanPool and L.A. Salter (2006). “Reconstructing the Flow of Information across Time and Space: A Phylogenetic Analysis of Ceramic Traditions from Prehispanic Western and Northern Mexico and the American Southwest”. In Lipo, C. P., M. J. O’Brien, M. Collard and S. J. Shennan, eds., Mapping our Ancestors. Phylogenetic Approaches in Anthropology and Prehistory. New Brunswick, N.J.: AldineTransaction.(209-30)

Härke, H. (1998). “Archaeologists and Migration: A Problem of Attitude?” Current Anthropology, 39: 19-45.

Hart, J.P. and J.E. Terrell, eds. (2002). “Darwin and Archaeology. A Handbook of Key Concepts”. Westport, CT.: Bergin & Garvey.

Hennig, W. (1965). “Phylogenetic Systematics”. Annual Review of Entomology, 10: 97-116.

Hennig, W. (1966). “Phylogenetic Systematics”. Chicago, IL.: University of Illinois Press.

Henrich, J. and P. Boyd (2002). “Why Cultural Evolution Does Not Require Replication of Representations”. Culture and Cognition,2: 87-112.

Hewlett, B. and L.L. Cavalli-Sforza (1986). “Cultural transmission among Aka pygmies”. American Anthropologist, 88: 922-34.

Hewlett, B., A. de Silvestri and C.R. Guglielmino (2002). “Semes and Genes in Africa”. Current Anthropology,43: 313-20.

Hildebrandt, H. (1873). “Den vetenskapeliga fornsforskningen, hennes uppgift, behof och rätt”. Stockholm: L. Norman.

Hildebrandt, H. (1880). “De förhistoriska folken I Europa. En handbok i jämförande fornunskap”. Stockholm: Jos. Seligmann & Co. Förlag.

Hodder, I., ed. (2001). “Archaeological Theory Today”. Cambridge: Polity.

Hoenigswald, H.M. and L.F. Wiener, eds. (1987). “Biological Metaphor and Cladistic Classification. An Interdisciplinary Perspective”. London: Frances Pinter (Publishers).

Högberg, A. (1999). “Child and Adult at a Knapping Area. A technological Flake Analysis of the Manufacture of a Neolithic Square Sectioned Axe and a Child’s Flintknapping Activities on an Assemblage excavated as Part of the Öresund Fixed Link Project”. Acta Archaeologica, 70: 79-106.

Hull, D.L. (1965). “The Effect of Essentialism on Taxonomy – Two Thousand Years of Stasis”. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 15: 314-26.

Huxley, J. (1943). “Evolution. The New Synthesis”. London: Allen & Unwin.

Ingold, T. (2000). “The poverty of selectionism”. Anthropology Today, 16: 1-2.

Ingold, T. (2007). “The trouble with ‘evolutionary biology'”. Anthropology Today, 23: 3-7.

Jablonka, E. and M.J. Lamb (2005). “Evolution in Four Dimensions: Genetic, Epigenetic, Behavioural, and Symbolic Variation in the History of Life”. Cambridge, MA.: Bradford Books.

Jablonka, E. and M.J. Lamb (2006). “The evolution of information in the major transitions”. Journal of Theoretical Biology,239: 236-46.

Klindt-Jensen, O. (1975). “A History of Scandinavian Archaeology”. London: Thames & Hudson.

Kuhn, S.L. (2004). “Evolutionary perspectives on technology and technological change”. World Archaeology, 36: 561-70.

Laland, K.N. and G.R. Brown (2002). “Sense & Nonsense. Evolutionary Perspectives on Human Behaviour”. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leonard, R.D. (2001). “Evolutionary Archaeology”. In Hodder, I., ed. Archaeological Theory Today. Cambridge: Polity.(65-97)

Leonard, R.D. and G.T. Jones (1987). “Elements of an Inclusive Evolutionary Model for Archaeology”. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 6: 199-219.

Lewontin, R.C. (1970). “The Units of Selection”. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 1: 1-14.

Lipo, C.P., M.J. O’Brien, M. Collard and S.J. Shennan, eds. (2006). “Mapping our Ancestors. Phylogenetic Approaches in Anthropology and Prehistory”. New Brunswick, N.J.: AldineTransaction.

Lyman, R.L. (2007). “What is the ‘process’ in cultural process and in processual archeology?” Anthropological Theory, 7: 217-50.

Lyman, R.L. and M.J. O’Brien (1997). “The Concept of Evolution in Early Twentieth Century Americanist Archaeology”. In Barton, C.M. and G.A. Clark, eds., Rediscovering Darwin: Evolutionary Theory and Archaeological Explanation. Washington, D.C.: Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association.(21-48)

Lyman, R.L. and M.J. O’Brien (1998). “The Goals of Evolutionary Archaeology. History and Explanation”. Current Anthropology,39: 615-52.

Lyman, R.L. and M.J. O’Brien (2000a). “Chronometers and Units in Early Archaeology and Palaeontology”. American Antiquity, 65: 691-707.

Lyman, R.L. and M.J. O’Brien (2000b). “Measuring and Explaining Change in Artifact Variation with Clade-Diversity Diagrams”. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 19: 39-74.

Lyman, R.L. and M.J. O’Brien (2003). “Cultural Traits: Units of Analysis in Early Twentieth-Century Anthropology”. Journal of Anthropological Research, 59: 225-50.

Lyman, R.L. and M.J. O’Brien (2004). “A History of Normative Theory in Americanist Archaeology”. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 11: 369-96.

Lyman, R.L. and M.J. O’Brien (2006). “Seriation and Cladistics: The Difference between Anagenetic and Cladogenetic Evolution”. In Lipo, C.P., M.J. O’Brien, M. Collard and S.J. Shennan, eds., Mapping our Ancestors. Phylogenetic Approaches in Anthropology and Prehistory. New Brunswick, N.J.: AldineTransaction.(65-88)

Lyman, R.L., M.J. O’Brien and R.C. Dunnell (1997a). “Americanist Culture History: Fundamentals of Time, Space, and Form”. New York, N.Y.: Plenum.

Lyman, R.L., M.J. O’Brien and R.C. Dunnell (1997b). “The Rise and Fall of Culture History”. New York, N.Y.: Plenum.

Lyman, R.L., S. Wolverton and M.J. O’Brien (1998). “Seriation, Superposition, and Interdigitation: A History of Americanist Graphic Depictions of Culture Change”. American Antiquity, 63: 239-61.

MacDonald, D.H. (1998). “Subsistence, sex, and cultural transmission in Folsom culture”. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 17: 217-39.

Mace, R., C.J. Holden and S.J. Shennan, eds. (2005). “The Evolution of Cultural Diversity. A Phylogenetic Approach”. London: UCL Press.

Maschner, H.D.G., ed. (1996). “Darwinian Archaeologies”. New York, N.J.: Plenum.

Mayr, E. (1957). “Species concepts and definitions”. In Mayr, E., ed. The Species Problem. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science.(1-22)

Mesoudi, A. (2007). “Using the methods of experimental social psychology to study cultural evolution”. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 1: 35-58.

Mesoudi, A., A. Whiten and K. Laland (2004). “Is Human Cultural Evolution Darwinian? Evidence Reviewed from the Perspective of The Origin of Species“. Evolution, 58: 1-11.

Mesoudi, A., A. Whiten and K.N. Laland (2006). “Towards a unified science of cultural evolution”. Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 29: 329-83.

Mesoudi, A., A. Whiten and K.N. Laland (2007). “Science, evolution and cultural anthropology. A response to Ingold”. Anthropology Today, 23: 18.

Milne, S.B. (2005). “Palaeo-Eskimo Novice Flintknapping in the Eastern Canadian Arctic”. Journal of Field Archaeology, 30: 329-46.

Montelius, G.O.A. (1903). “Die Typologische Methode”. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wicksell.

Nordenskiöld, E. (1926). “Die Geschichte der Biologie. Ein Überblick”. Jena: Verlag von Gustav Fischer.

O’Brien, M.J., ed. (1996). “Evolutionary Archaeology: Theory and Application”. Salt Lake City, UT.: University of Utah Press.

O’Brien, M.J., ed. (in press). “Cultural Transmission and Archaeology: Issues and Case Studies “. Washington, D.C.: Society for American Archaeology Press.

O’Brien, M.J. and R.L. Lyman (1999). “Seriation, Stratigraphy, and Index Fossils. The Backbone of Archaeological Dating”. New York, N.Y.: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

O’Brien, M.J. and R.L. Lyman (2000a). “Evolutionary Archaeology. Reconstructing and Explaining Historical Lineages”. In Schiffer, M.B., ed. Social Theory in Archaeology. Salt Lake City, UT.: University of Utah Press.(126-42)

O’Brien, M.J. and R.L. Lyman (2000b). “Applying Evolutionary Archaeology. A Systematic Approach”. New York, N.Y.: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

O’Brien, M.J. and R.L. Lyman (2002). “Evolutionary Archaeology: Current Status and Future Prospects”. Evolutionary Anthropology,11: 26-36.

O’Brien, M.J. and R.L. Lyman (2003). “Resolving phylogeny: Evolutionary archaeology’s fundamental issue”. In Vanpool, T.L. and C.S. Vanpool, eds., Essential Tensions in Archaeological Method and Theory. Salt Lake City, UT.: University of Utah Press.(115-35)

O’Brien, M.J. and R.L. Lyman (2004). “History and Explanation in Archaeology”. Anthropological Theory, 4: 173-97.

O’Brien, M.J., R.L. Lyman and R.D. Leonard (1998). “Basic Incompatibilities between Evolutionary and Behavioral Archaeology”. American Antiquity, 63: 485.

O’Brien, M.J., J. Darwent and R.L. Lyman (2001). “Cladistics is useful for reconstructing archaeological phylogenies: Paleoindian points from the southeastern United States”. Journal of Archaeological Science, 28: 1115-36.

O’Brien, M.J., R.L. Lyman and M.B. Schiffer (2005). “Archaeology as a Process: Processualism and its Progeny”. Salt Lake City, UT.: The University of Utah Press.

O’Brien, M.J., R.L. Lyman, D.S. Glover and J. Darwent (2003). “Cladistics and Archaeology”. Salt Lake City, UT.: University of Utah Press.

O’Brien, M.J., R.L. Lyman, Y. Saab, E. Saab, J. J. Darwent and D.S. Glover (2002). “Two issues in archaeological phylogenetics: Taxon construction and outgroup selection”. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 215: 133-50.

Odling-Smee, F.J., K.N. Laland and M.W. Feldman (2003). “Niche Construction. The Neglected Process in Evolution”. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Pigeot, N. (1990). “Technical and Social Actors: Flinknapping Specialists at Magdalenian Etiolles”. Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 9: 126-41.

Platnick, N.I. and H.D. Cameron (1977). “Cladistic Methods in Textual, Linguistic, and Phylogenetic Analysis”. Systematic Biology, 26: 380-85.

Ramenofsky, A.F. and A. Steffen, eds. (1998). “Unit Issues in Archaeology: Measuring Time, Space, and Material”. Salt Lake City, UT.: University of Utah Press.

Richerson, P.J. and R. Boyd (2005). “Not by genes alone: how culture transformed human evolution”. Chicago, IL.: University of Chicago Press.

Ridley, M. (1986). “Evolution and Classification: The Reformation of Cladism”. Harlow: Longman.

Riede, F. (2006a). “Chaîne Opèratoire – Chaîne Evolutionaire. Putting Technological Sequences in Evolutionary Context”. Archaeological Review from Cambridge, 21: 50-75.

Riede, F. (2006b). “The Scandinavian Connection. The Roots of Darwinian Thinking in 19th Century Scandinavian Archaeology”. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 16: 4-19.

Riede, F. (2007a). “Maglemosian Memes: Technological Ontology, Craft Traditions and the Evolution of Northern European Barbed Points”. In O’Brien, M.J., ed. Cultural Transmission and Archaeology: Issues and Case Studies. Washington, D.C.: Society for American Archaeology Press.(in press)

Riede, F. (2007b) “Reclaiming the Northern Wastes – An Integrated Darwinian Re-Examination of the Earliest Postglacial Recolonization of Southern Scandinavia”. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge.

Rosenberg, M. (1994). “Pattern, Process, and Hierarchy in the Evolution of Culture”. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology,13: 307-40.

Schoch, M., ed. (1997). “Oscar Montelius: Die Typologische Methode”. Munich: Documenta Historiae.

Shennan, S.J. (1989). “Archaeology as archaeology or as anthropology? Clarke’s Analytical Archaeology and the Binfords’ New perspectives in archaeology 21 years on”. Antiquity, 63: 831-35.

Shennan, S.J. (1996). “Social Inequality and the Transmission of Cultural Traditions in Forager Societies”. In Steele, J. and S.J. Shennan, eds., The Archaeology of Human Ancestry: Power, Sex and Tradition. London: Routledge.(365-79)

Shennan, S.J. (2000). “Population, Culture History, and the Dynamics of Culture Change”. Current Anthropology, 41: 811-35.

Shennan, S.J. (2002). “Genes, Memes and Human History: Darwinian Archaeology and Cultural Evolution”. London: Thames and Hudson.

Shennan, S.J. (2004). “Analytical Archaeology”. In Bintliff, J., ed. A Companion to Archaeology. Oxford: Blackwell.(3-20)

Shennan, S.J. (2005). “Culture, society and evolutionary theory”. Archaeological Dialogues, 11: 107-14.

Shennan, S.J. (2006). “From Cultural History to Cultural Evolution: An Archaeological Perspective on Social Information Transmission”. In Wells, J.C.K., S. Strickland and K.N. Laland, eds., Social Information Transmission and Human Biology. London: CRC Press.(173-90)

Shennan, S.J., ed. (in press). “Pattern and Process in Cultural Evolution”. London: University of London Press.

Shennan, S.J. and J. Steele (1999). “Cultural learning in hominids: a behavioural ecological approach”. In Box, H.O. and K.R. Gibson, eds., Mammalian Social Learning: Comparative and Ecological Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.(367-88)

Skelton, P., A. Smith and N. Monks (2002). “Cladistics: A Practical Primer on CD-ROM”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, E.A. (2001). “Three styles in the evolutionary analysis of human behaviour “. In Cronk, L., N. Chagnon and W. Irons, eds., Adaptation and Human Behaviour. New York, N.Y.: Aldine de Gruyter.(27-46)

Sober, E. (1993). “Philosophy of Biology”. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stott, R. (2003). “Darwin and the Barnacle”. London: Faber.

Teltser, P.A., ed. (1995). “Evolutionary Archaeology: Methodological Issues”. Tucson, AZ.: The University of Arizona Press.

Trigger, B.G. (1989). “A History of Archaeological Thought”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tschauner, H. (1994). “Archaeological systematics and cultural evolution: retrieving the honour of culture history”. Man N.S.,29: 77-93.

Wells, J.C.K., S. Strickland and K.N. Laland, eds. (2006). “Social Information Transmission and Human Biology”. London: CRC Press.