Communication

Etymologically, ‘communication’ is traced back to the Latin root– communicare – meaning ‘to share’ or ‘to be in relation with’ or traced to communicatio, itself linked to the Latin munus (duty, gift). The notion of communication, as well as the discussion of the notion, has been present in the West from pre-Socratic times. Yet it was only in the twentieth century, with the development of a fully-fledged ‘communication theory’, communication was fundamentally conceived in terms of

Sender → Message → Receiver

The message provides the basis for this action since it is encoded by the sender and decoded by the receiver. The fact that it requires coding and encoding, of course, indicates that the message is not a perfect, transparent vehicle for ‘meaning’: it mediates meaning as a result of being in a channel. The work of researchers in cybernetics in the late 1940s led to an ‘information theoretic’ theory of communication in which ‘meaning’ of communications was deemed irrelevant and the actions of an information source, a message, a transmitter, a signal, a receiver, a message, a destination, “noise” were the crucial factors.

However, communication is also understood outside information theory, particularly in the humanities, as involving the delivery of more or less clear messages between a sender and a receiver. In literary and poetic communication, in contrast to information theory, ‘meaning’ plus the roles of the ‘sender’ and the ‘receiver’ of a message, along with codes, are deemed very important.

A mediating position on between the ‘neutral’ and ‘meaningful’ understanding of communication has been the disciplinary field of semiotics. Originally prominent in dealing with communication involving only human signs in a manner of cultural anthropology, semiotics developed in a fashion which was to re-cast understandings of communication. In particular in the late twentieth century, Thomas A. Sebeok’s increasing attention to non-human communication as he developed ‘zoosemiotics’ marks a period of great advance in the theorising of communication in general. With the realisation that the overwhelming amount of communication in the world is nonverbal, as opposed to a relatively minuscule amount of verbal (human only) communication, Sebeok continually attempted to draw the attention of glottocentric communication theorists to the larger framework in which human verbal communication is embedded. As Sebeok demonstrates, when one starts to conceive of communication in the aggressive expressions of animals or the messages that pass between organisms as lowly as the humble cell, rather than just in, say, messages in films or novels, then the sheer number of transmissions of messages (between components in any animal’s body, for example) becomes almost ineffable. This amounts to a major re-orientation for communication. Human affairs are found to represent only a small part of communication in general.

Definitions of communication commonly refer to etymology. Usually, this involves noting that the Latin root of ‘communication’ – communicare – means ‘to share’ or ‘to be in relation with’ and has its own relations in English to ‘common,’ ‘commune,’ and ‘community,’ suggesting an act of ‘bringing together.’ (cf. Cobley 2008, Rosengren 2001: 1; Schement 1993: 11; Beattie 1981: 34 ). Yet, this seemingly inclusive and broad definition of communication is not the only one that arises from the invocation of etymology. Peters (2008; cf. Craig 2000), somewhat differently, notes that ‘communication’ arises from the Latin noun communicatio, meaning a ‘sharing’ or ‘imparting’: arguably, this has little relation to terms such as union or unity, but rather links to the Latin munus (duty, gift). As such, its root senses have to do with change, exchange, and goods possessed by a number of people.

The notion of communication, as well as the discussion of the notion, has been present in the West from pre-Socratic times. The Hippocratic corpus, for example, is a list of symptoms and diseases; it discusses ways of ‘bringing together’ the signs of a disease or ailment with the disease itself for the purposes of diagnosis and prognosis. Hippocrates’ work clearly drew on the nascent idea of communication evident in the thought of the pre-Socratics. Later, classic works of Greek philosophy also explored communication (Peters 1999: 36-50), focusing, especially and in contrast to the pre-Socratics, on communication associated with the word: orality and literacy.

Classic Greek philosophy, emerging from a society in the transition from oral to literate modes, set much of the tone for the West’s understanding of communication. Like many societies, early Greece was characterised by orality. This involved communication by means of the voice, without the technology of writing. Oral communication, because it could not store information in the same ways and amounts as writing, evolved mnemonic, often poetic, devices to pass on traditions and cultural practices. Narrative, for example, developed as a form of communication in which facts were figured as stories of human action to be retold in relatively small public gatherings of people.

The development of literate societies involved communication which was both better suited to the storage of large amounts of information and to the recording of abstract, scientific principles. Written communication is originally thought to have developed as a means of keeping a record of economic transactions. In literate societies, written communication was subsequently also used for the reification of cultural and religious traditions. Writing wrought a transformation in the experience of space and time: in contrast to oral messages, a communication in writing could be read at a later date than its composition; it could also be consumed in private. In tandem with these transformations, written communication facilitated scientific thought and the growth of technology, providing a means of knowledge storage that far surpassed in its capacity for detail and complexity, that of oral memory.

Religious tradition was particularly important in the development of written communication. Latin writers from Augustine to Aquinas were not only concerned with scriptural exegesis but also contributed to the theorisation of the relation between signs and referents. In pre-print Europe, the protection of religious tradition was partnered by the preservation of writing; the centuries before Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press witnessed writing as the preserve of monasteries, the locations in which scriptures were copied out longhand.

The society of post-print Europe experienced major transformations of social life in which communication played a central role. In the centuries after 1450 there was a significant growth in literacy and, as a consequence, a period in which the dissemination of communication took place on a scale never witnessed before. Yet print communication did not yet experience the boom that began in the late seventeenth century. In England, for example, the Licensing Act severely regulated and censored printed publications of all sorts. With the lapsing of the act in 1695 a range of printed artefacts could be produced for prospective markets and access to printing technology was sought by entrepreneurs (Williams 1985: 203-206; Hunter 1990: 193). Booksellers grew in number. The subsequent growth of magazines, periodicals, newspapers and other printed materials also aided literacy, whether in schools or when taken up privately by the self-taught citizen. Print promoted a more private, individual communication centred on the self. Yet, through its reach to a large audience, it also allowed public life in Europe to prosper.

In the wake of printed communication, the activities of public life took on a different complexion in the eighteenth century, developing into what Habermas (1989) calls the (bourgeois) public sphere. This sphere, derived from the meetings of the mercantile class, burghers and others, for talk and debate, developed in the seventeenth century but accelerated especially in the eighteenth century and was attendant on an explosive growth of coffeehouses in Britain and the German-speaking lands and, in France, the salons. The importance of the discourse in these arenas sits deeper than its surface appearance. As Habermas shows, the coffeehouse talk was mainly orientated towards questions of literature, even above politics. Yet, such talk, importantly, took place in a domain divorced from the family and the intimate sphere while, at the same time, being extraneous to reproduction (that is, the reproduction of the relations of production, commerce and business). As such, it exemplified the bourgeoisie and its ability to pursue leisure in the period, yet it also had another complexion deriving from the fact that the bourgeoisie had not become entrenched in the way that it was to become in the following century in Europe. This entailed that the discourse of the public sphere was political in quite a ‘pure’ sense, a ‘rational’ communication, as described by Habermas, not simply dictated by, or the epiphenomenon of, the accumulation of capital.

Public sphere communication was not only located in the coffeehouses, it was also replicated and disseminated in the journals of the day, specifically in Britain, The Tatler and The Spectator. Conversation – oral communication – was thus stimulated by print communication during the period, and vice versa. Among the educated classes in eighteenth-century Europe, oral communication assumed an importance which far surpasses that of the present day Western world of mobile telephony and wireless connection. The importance of the ‘public sphere thesis’ to understanding communication is that it again exemplifies the ways in which entities are brought together: in this case, members of a particular literate class.

A fully-fledged ‘communication theory’ emerged in the twentieth century and was, not coincidentally, intimately linked to investigations of a similar kind of ‘togetherness’ in a number of different fields. Among these investigations were those of American sociology (the Chicago School) and the written accounts of Anglophone anthropology (especially, Malinowski, Boas and Sapir) which, along with assessments of the idea of ‘community’ (for example, Tönnies), attempted to present a comprehensive vision of how communication was constituted. These early milestones in the development of the human sciences were accelerated in the 1920s by a series of researches into specific aspects of modern communication and communication as a whole (see Peters 1999). New technologies of communication during the period stimulated the broadening of the understanding of communication. Photography, in various forms, had proliferated since 1839; film, from the mid-1890s, had become an important new medium of information and entertainment; and, radio, above all, became the defining medium in which communication of one to many – broadcasting, or mass communication – could take place without listeners having to even leave their homes.

Radio was an intensely public medium of communication and stimulated worries about its potential uses in propaganda. Put another way, there was concern about the specific deleterious ways in which its communication could bring people together. The period from the 1920s to the late 1940s, a period dominated by the use of radio for propagandizing purposes by the Nazis and the fascists in Europe, featured a renewal and expansion of the understanding of communication by intellectuals. Political scientists and theorists of the ‘public’ (for example, Lippman, Bernays, Schmitt, Lasswell) were aligned with ‘administrative researchers’ (for example, Lasswell, Berelson) who carried out industry-funded studies of (usually) media audiences in re-defining the players and factors in communication.

The understanding of communication in this period generally proceeded from the flow of

Sender → Message → Receiver

What are brought together in this model, in the most fundamental sense, are the sender and receiver, or addresser and addressee. The message provides the basis for this action since it is encoded by the sender and decoded by the receiver. The fact that it requires coding and encoding, of course, indicates that the message is not a perfect, transparent vehicle for ‘meaning’: it mediates meaning as a result of being in a channel. Lasswell also presupposes that communication has ‘effects’ in the formula “Who, says what, in which channel, to whom, with what effect”. Certainly, the Payne Fund studies of movies in 1930s America proceeded from an idea of communication in which movies were believed to have some effects on their viewers (in this case, children) and that it was the job of communication research to enumerate and evaluate such effects.

Despite the assumption of ‘effects’, the work of Lasswell and others represents a ‘scientific’, de-personalized understanding of communication. The work of researchers in cybernetics in the late 1940s offers a more ‘objective’ account of communication, still. In his research for the Bell telecommunications company, later popularised by and in collaboration with Warren Weaver, Claude Shannon presented a highly influential model of the communications process in which ‘transmission’ is the key feature. An information source in the model, with a message, uses a transmitter to produce a signal, which is received, by a receiver, which delivers a concomitant message to a destination. At the interface of the sent signal and the received signal, Shannon and Weaver (1949) show, is likely to be “noise”. Such “noise” is a factor that might corrupt the implicitly mythical integrity of the message in transmission, the prime example being many conflicting signals in the same channel at once. It is a difficulty in the study of communication which has been revisited by numerous attempts to construct communication models.

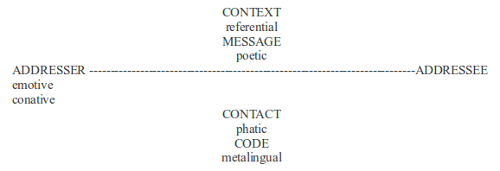

Clearly motivated by information theory and Shannon in particular, Roman Jakobson (1960) produced a model of communication which, while it focuses on poetry and stylistics, has been enormously influential in contemporary understandings of communication, largely because it does shed light on everyday communication. In outline, it features a linear communication from Addresser to Addressee, much in the manner of a ‘Sender-Message-Receiver’ model of the kind that Shannon and Weaver made more sophisticated. Jakobson’s model suggests, however, that communication is traversed by functions. Thus, as diagrammatized here,

communication takes place with reference to six components (addresser, addressee, context, message, contact, code) each of which has a ‘function’ (signalling the legacy of the Prague Linguistics Circle, as well as Bühler) assigned to it. Thus, communication can take place with reference to each of the components with an orientation to one or more of them being dominant. If there is orientation to the context then the referential function dominates; if their is orientation to the message, there is a dominating poetic function; if to the addresser, an emotive function; if to the addressee, a conative or imperative function; if to the contact, a phatic function (in the classic sense of Malinowski); if to the code, a metalingual function, referring to the means by which the communication attempts to take place.

In a way, Jakobson’s functions are embodiments of ‘noise’ since they indicate that there is no such thing as the neutral message that lies at the heart of information theory’s conception of communication. Gerbner’s 1956 model attempts to circumvent the problems of over-emphasizing the integrity of the message in communication by exploring the roles of ‘selection’, ‘availability’ and ‘context’. The 1957 model of Westley and MacLean, on the other hand, decreases its generality by focussing on journalism. Interestingly, it seems that there was a desire to unravel the components of communication to determine which elements and which intersections of elements in the communication act might be susceptible to the cause of misunderstanding.

Certainly, this preoccupation in communication theory has achieved an unsettling of straightforward relations of the sender and receiver. At the very least, communication theory’s influence on conceptualisation of the arts in particular has been such that a model of ‘creator, work, reception’ can only be considered where due attention is paid to each component in the transaction. In the second half of the twentieth century, further advances in the technology of communication invited specific focus on media to explicate what communication is. All communication is mediated by virtue of the fact that telepathy for humans and direct messages for other organisms have not been achieved. Yet radio was supplemented, especially after the 1950s, by television, a powerful medium of mass communication in that it not only allowed the flow of aural messages into the domestic environment but provided an audio-visual technology which was to become the focus of many homes. ‘Medium theorists’, observing such developments, stressed that media are, in the phrase made famous by the Canadian communication theorist, Marshall McLuhan, ‘extensions’ of humans. Like tools, media extend the capabilities of humans to enable them to reach out into a broader world of communication. However, the corollary of this is that they transform the human’s apprehension of the world and produce a consciousness that is tied to that particular medium, for example orality and literacy. For medium theorists (Innis, McLuhan, Havelock, Ong, Meyrowitz, Postman, Levinson et al) all the major media have entailed ‘paradigm shifts in cultural systems’ (see Danesi 2002). However, in a sense, medium theory does share with other communication theory, especially study of the media latterly, a concern with how audiences are bound up in the process of mediation. It is the consciousness of media users that is transformed.

The tendency to understand communication as having an ‘effect’ also implicates audiences, although this becomes so much clearer in considering theories of communication which are skeptical about effects. In the 1950s, ‘uses and gratifications’ approaches to communication found that audiences utilise communications media in ways that do not simply result in linear effects. Katz and Lazarsfeld, for example, put forward the idea of a “two-step flow” in communication, replacing the image of the audience as a set of unconnected individuals with a theory of ‘opinion leaders’, those who are more exposed to the media, circulating messages from the media which disseminate influence on this local basis (see Katz 1957). More forceful, still, was the analysis of the sociologist Joseph Klapper which stressed minimal effects of mass communication. For Klapper (1960), exposure to the typically large amounts of mass communication characteristic of modernity would be more likely to reinforce existing attitudes rather than to coerce communication receivers into adopting attitudes they did not harbour hitherto. As such, ‘effects’ of communication were found to be negligible.

From the early 1980s onwards, the importance of studying audiences apart from ‘effects’ became imperative. Televisual communication had established itself in Western homes, yet it was to be supplemented by video (in the form of domestic VCRs), which potentially offered greater autonomy to viewers through the capacity of ‘timeshift’. Research into communication in the medium of television demonstrated that viewers were not necessarily behaving as expected in response to televisual communication; indeed, active television sets in homes were often found to be totally ignored. ‘Timeshift’ allowed viewers to receive televisual communication on an extended basis, repeatedly if chosen, and at times different to those of the original broadcast. Research into communication during this period recapitulated the lessons of ‘uses and gratifications’ approaches, although often in a more critical manner (for example, Morley 1980, Hobson 1982). The audience was frequently found to be the locus of attitudes, values, experiences – ideological baggage that is brought to the act of decoding. As a result, audience members were found to actively and immediately reshape the communications they received, thoroughly transforming them in a manner that tended to invalidate the idea of a neutral encoded message being decoded by a receiver. Audiences did not simply decode communication, then; it could be argued that they ‘made’ (or, at least, ‘re-made’) it. In such instances, what were brought together in communication were the members of communities of interpretation.

The proliferation of communication technologies in the twentieth century re-fashioned the way in which communication was carried out and also forced revisions of the way in which communication was to be theorised. Computers, especially their adoption as occupational and domestic media, contributed to a ‘digitalising’ of communication, despite the naturalizing of their analogue, graphic user interfaces. The use of computers for internet access, along with the implementation of hypertext links, created the potential of non-linear communication. Yet, as Giddens and others observed, some traditional aspects of face-to-face communication were revamped through the ‘time-space compression’ which allowed global communication to take place so rapidly (email, video conferencing and so forth). The key paradox of global communication, however, is the fact that the proliferation of digital technologies seems to suggest that there is more opportunity for humans to communicate with growing numbers of humans than before. This proliferates through the convergence of computers, the internet, television, mobile communications technologies (include computers), music technologies, and email. At the same time, though, the profusion of technologies means that global communication evinces a fundamental unbalance between those who can afford converged technologies and those who cannot (many of whom are the very labourers in the Third World whose low-waged endeavour makes converged communication possible for consumers in the West).

In terms of understanding what communication is, globalization has at least suggested that signs are omnipresent and that it is necessary to study them in all their manifestations if communication is to be understood. In the late twentieth century, semiotics, based on various pre-Socratic principles, underwent a resurgence and spearheaded new understandings in the study of communication. Taken up initially in the study of media communication, semiotics demonstrated that the basic functioning of communication could be identified in the vagaries of (invariably verbal) signs. Yet Thomas A. Sebeok’s increasing attention to non-human communication as he developed ‘zoosemiotics’ marks a period of great advance in the theorising of communication in general. With the realisation that the overwhelming amount of communication in the world is nonverbal, as opposed to a relatively minuscule amount of verbal communication, Sebeok identified “terminological chaos in the sciences of communication, which is manifoldly compounded when the multifarious message systems employed by millions of species of languageless creatures, as well as the communicative processes inside organisms, are additionally taken into account” (1991: 23). From his zoosemiotic period onwards, Sebeok continually attempted to draw the attention of glottocentric communication theorists to the larger framework in which human verbal communication is embedded. As Sebeok demonstrates (1997), when one starts to conceive of communication in the aggressive expressions of animals or the messages that pass between organisms as lowly as the humble cell, rather than just in, say, messages in films or novels, then the sheer number of transmissions of messages (between components in any animal’s body, for example) becomes almost ineffable. This amounts to a major re-orientation for communication. Human affairs are found to represent only a small part of communication in general.

Bibliography

Beattie, E. (1981) ‘Confused terminology in the field of communication, information and mass media: brillig but mimsy’, Canadian Journal of Communication, 8 (1): 32-55.

Cobley, P. (2008) ‘Communication: definition and concepts’ in W. Donsbach (ed.) International Encyclopedia of Communication, Vol. II. Malden, MA.: Blackwell, pp. 660-666.

Craig, R. T. (2000) ‘Communication’ in T. O. Sloane (ed.) Encyclopedia of Rhetoric, New York: Oxford University Press.

Danesi, M. (2002). Understanding Media Semiotics London: Arnold.

Gerbner, G. (1956) ‘Toward a general model of communication’ Audio-Visual Communication Review 4: 171-99

Habermas, J. (1989) Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society trans. T. Burger and F. Lawrence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hobson, D. (1982) Crossroads: The Drama of a Soap Opera London: Methuen.

Hunter, J. P. (1990) Before Novels: The Cultural Contexts of Eighteenth-Century Fiction New York and London: Norton.

Indiana University Press, pp. 22-35.

Jakobson, R. (1960) ‘Closing statement: linguistics and poetics’ in T. A. Sebeok (ed.) Style in Language, Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

Katz, Elihu (1957) ‘The two-step flow of communication’ Public Opinion Quarterly (Spring): 61-78

Klapper, J. T. (1960) The Effects of Mass Communication New York: Free Press.

Lasswell, H. (1948) ‘The structure and function of communication in society’ in L. Bryson ed., The Communication of Ideas New York: Institute for Religious and Social Studies pp 37-51

Morley, D. (1980) The Nationwide Audience London: B.F.I.

Peters, J. D. (1999) Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Peters, J. D. (2008) ‘Communication: history of the idea’ in W. Donsbach (ed.) International Encyclopedia of Communication, Vol. II. Malden, MA.: Blackwell, pp. 689-693.

Rosengren, K. E. (2000) Communication: A n I ntroduction, London and Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Schement, J. R. (1993) ‘Communication and information’ in J. R. Schement and B. D. Ruben (eds.) Between C ommunication and I nformation. Information and B ehaviour.Vol. 4. New York: Transaction, pp. 3-34.

Sebeok, T. A. (1997) ‘The evolution of semiosis’ in R. Posner et al (eds.), Semiotics: A Handbook on the Sign-Theoretic Foundations of Nature and Culture.Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 436-446

Sebeok, T. A.(1991) ‘Communication’ in A Sign is Just a Sign, Bloomington:

Shannon, C. E. and Weaver, W. (1949) The Mathematical Theory of Communication Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Westley, B. and MacLean, M. (1957) ‘A conceptual model for communication research’ Journalism Quarterly 34: 31-8.

Williams, G. (1985) ‘Newsbooks and popular narrative during the middle of the seventeenth century’ in J. Hawthorn ed., Narrative: From Malory to Motion Pictures London: Edward Arnold.