Intonation's many functions

Philippe Martin

French Studies

University of Toronto

Abstract

For the non-linguist, intonation is often thought of as a feature of human voice which conveys emotions and attitudes. Yet Intonation has another – although considered marginal by linguists – role in speech: to indicate the declarative or interrogative sentence modality and its many variants (whose linguistic status is often debatable). But intonation is also heavily conditioned by linguistic rules, specific to each language, respected by the speaker even in the most severe physical conditions of speech production.

Intonation in the (linguistic) system

When we speak, when

we read, even silently, a musical movement inevitably accompanies our words,

constituting the sentence intonation. For a long time, linguists have relegated

this music of the sentence to the study of emotions and social attitudes, with

the exception of a very limited part given in the language system, with the

indication of the declarative or interrogative modality of the sentence.

In fact, this is not very

different from other phonological objects such as vowels and consonants, which

obviously have to be produced through muscular activities interacting with the

speaker general emotional state. Their realizations follow linguistic rules but

reflect as well the emotions and attitudes of the speaker.

Still, most recent studies

on intonation and emotions are heavily depending on empirical data, and not on

any phonological insight. Typical studies merely comment various statistical

study on global or local aspects of intonation, such as the average laryngeal

frequency, the variations of tempo, and the like. By doing so, these efforts

maintain the old tradition, denying phonological character to intonational

objects. But intonation is as linguistic as vowels and consonants. Its minimal

units - such as pitch contours located on stressed syllables - are sensitive in

their realization to the emotional state of the speaker, yet they maintain a

rigorous system of contrast with each other as other phonological units do.

In

this sense, speaking as any other human socialized activity results from the

filtering (shaping) of primary impulses which have to undergo social filtering

but which nevertheless constitute the only source of energy. What is remarkable

is that, like in the example of walking, some large liberty is given to each

individual as long as the social constraints are respected. Going over these

constraints leads to various sanctions, from pair mockery to severe legal

penalties.

This is true even in

adverse speech production conditions, such as created by intense physical

activity, extreme emotional distress, etc., when these conditions prevent us to

meet the numerous physical (muscular) constrains involved in speech production.

We all know some of these conditions by experience, when we run out of breathe

after a long run or swim, of while crying following a severe emotional shock. Of

course all speech production units such as the phoneme realizations will be

affected in those conditions, but the most likely to be disturbed will be the

elements whose production involves time and rhythm.

Phoneticians have been

generally dealing with the second process, trying for instance to describe

empirically the detailed acoustical features of some regional variety of

intonation. Phonologists, at least those with some structural background, aim to

explain the minimal set of features that should be found in speech contours in

order to fulfill its assumed function(s).

Dominant North American

intonation researchers, however, tend to mix both attitudes, as they generally

start as phoneticians to get a sufficient empirical description, and then as

phonologists to find rules that would generate all the well-formed sequences of

contours in a sentence. Of course, acting this way, and using an a priori

notation system such as ToBI to represent empirical data, their approach is

somewhat biased from the beginning, as they will only take into account in their

phonology the data retained in their representation system in the first place.

But let's not tell them as such contradiction makes them very unhappy and can

lead at times to violent reactions.

For our part, we will start

the opposite way, in giving roles – functions – to sentence intonation which

should appear as reasonable hypotheses, but as such which cannot be proved (in

mathematical logic they would be called axioms). These hypotheses pertain to the

following linguistic content:

Despite this, the prosodic

structure is associated to the syntactic structure with the following

constraints:

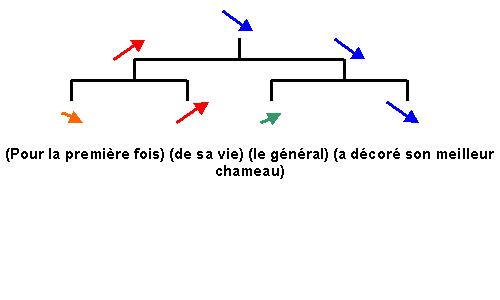

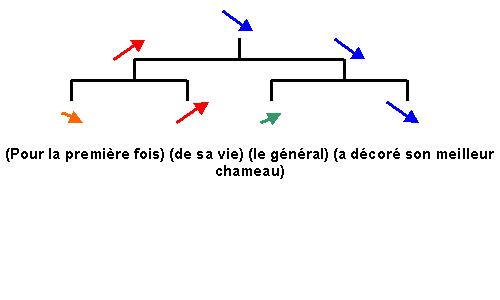

(For the first time of his

life, the general has decorated his best camel)

All the rules given above lead to a final result, among all possible sequences of melodic contours. Once the stress assigned to specific syllables, the principle of contrast of slope (which applies only to French) defines on each stressed syllable a pitch contour with a slope inverse to the slope of its immediately dominant contour on its right. In a group (A B), the pitch contour on A will be rising if B is falling, and falling if B is rising. Applied iteratively on the above example, assuming that the prosodic structure is congruent o the syntactic structure, we have:

First the dominant contour of

modality is assigned to the root of the prosodic structure (red arrow).

Secondly, at the left first level node a rising contour (in red) opposed to the

dominant blue modality contour is assigned. Finally we assign at the last level,

a falling contour (in brown) dominated by the red rising contour and a rising

contour (in green) dominated by its right neighbor.

The resulting sequence of

pitch contours assigned to effectively stressed syllables of the example is thus

fall, rise, rise and fall. A further constrain, linked to the stress levels,

differentiate by the level of pitch amplitude (i.e. the excursion range of the

fundamental frequency on the voiced part of the syllable) contours of same slope

which could appear at the same place (i.e. on the same stressed syllable)

encoding thus another prosodic structure. The first falling contour for instance

must be different from a falling declarative modality, and the second (red)

contour has to contrast with the third (in green) as located at another level in

the prosodic structure.

This sequence of melodic contours is specific to French. An Italian equivalent of the example, showing a very similar syntactic structure, would give totally different results (Martin, 1999).

The

many features of prosodic contours

Although limited in

numbers, more than one prosodic feature can be used by the speaker in a specific

linguistic system to encode the system of contrasts existing in the prosodic

structure, first to ensure the specificity of stressed syllables opposed to

un-stressed, second to indicate the hierarchical organization of the prosodic

“chunks” in the sentence.

In order of frequency of

use, we have:

-

Syllable duration, specifically

used to contrast un-stressed vowels with stressed ones, and frequently to signal

the final stressed syllables among the non-final ones;

-

Fundamental frequency movement,

rise of fall;

-

Syllable intensity;

-

Fundamental frequency level,

contrasting with the average level in the sentence along the declination line;

-

Specific pitch movements along the

overall contour in the stressed syllable, such as a contour final limited fall

for rising contours, and limited rise for falling contours;

-

Vowel quality, modifying slightly

(on considerably in the case of languages such as English or European

Portuguese) the quality of the vowel;

-

etc.

While speaking, some of

these features may be too expensive to use due to a severe competition with

physical or emotional constrains. A depression state of the speaker is a

classical example, as reflected by a slower speech rate and reduced pitch change

in the course of the sentence. All stressed prosodic contours will show a very

limited frequency excursion or be completely flat, and duration will be the most

important feature used to contrast prosodic contours in the sentence.

Another example is

whispered speech. No vocal fold vibration takes place and voicing of stressed

syllables cannot be performed. Stressed syllables contrast then by some

remaining features, such as duration and intensity.

Opposite examples pertain

to speech production in noisy environments. The speaker then can exaggerate the

coding of stress, using all possible features allowed in the linguistic system,

large frequency excursions and duration contrasts, possible use of idiosyncratic

pitch movements, etc. An extreme example is given by singers of pop music, who

have to invent original pitch variations on their stressed (and un-stressed)

syllables in order to stand out vocally from the usually very loud background

and develop a proprietary voice style easily recognizable.

Intonation

many hats

In summary, as for any

other phonological unit such as vowels and consonants, the speaker has to comply

with linguistic rules as well as with imitation rules. Linguistic rules are

followed in order to convey the information encoded in the discourse by helping

the listener in the syntactic parsing process by a appropriate prosodic

structure, and imitation rules are followed to mark the belonging of the speaker

to a specified social and geographic group.

References

Fonagy I. (1983), La Vive Voix,

Paris, Payot.

Léon P. (1993), Précis de

phonostylistique, parole et expressivité, Paris, Nathan.

Martin, Ph. (1999) Prosodie des

langues romanes : Analyse phonétique et phonologie », Recherches

sur le français parlé, Publications de l’Université de Provence, 1999

No 15, pp. 233-253.

Martin,

Ph. (2000) "L'intonation en parole spontanée", "Revue Française

de Linguistique Appliquée", Vol. IV-2, pp. 57-76, Paris.