Meet your publisher: a post-scriptum

“Backward I see in my own days where I sweated through fog with linguists and contenders, I have no mockings or arguments, I witness and wait. “ — Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself” […]

“Backward I see in my own days where I sweated through fog with linguists and contenders, I have no mockings or arguments, I witness and wait. “ — Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself” […]

In this editorial and the accompanying three texts we present a certain take on analyzing the details of communication in the media, a perspective now often described as the media talk approach (see Hutchby 2006; […]

By Dylann McLean For geographer John-David Dewsbury (2011), affective geography— which builds out of the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza and, later, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (see Deleuze and Guattari 1986) — is about forming […]

25? There are different ways of calculating a person’s age: from birth, or from the moment of conception. The same goes for institutions, organizations, associations, though for the latter ‘conception’ is harder to pin down, […]

This began as an exploration of messages in our society. How do we develop these messages? Produce and distribute these messages? What are the aesthetic principles to these messages? I’m searching for a bloodline that rings throughout the entire platform of communication tactics, hoping that the sum is directly reflective when analyzing its parts. I started out thinking about these messages objectively but was quick to realize that when dealing with messages, you’re not just looking at how a sign looks and where it’s placed; you’re dealing with its words and indefinitely words aren’t without their healthy dose of subtext. This isn’t simply an exploration into messages; this is a scope into communication, leading to ideals, leading to communities, leading to humanity. Messages are representative of us, a modern trail of breadcrumbs, leading us to what we hope will manifest itself into validity or some sort of raw truth. […]

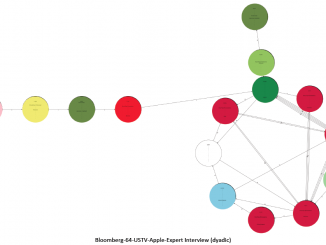

One of the major challenges in the development of software for multimodal analysis is the variety of media types and data which such software must handle. Software development, as with the human sciences, have tended towards compartmentalization during what Halliday referred to (1991: 39) as ‘the age of disciplines’, thus most relevant software applications tend to operate on specific types of data or provide specific tools for particular tasks. An intrinsic problem for multimodal digital software then is the computational integration of resources for the analysis of written text, image, sound, video, hypermedia and potentially any other media of communication (cf. Schmidt et. al. on software interoperability). […]

So often, in language origins discussions, the ‘target to be explained in evolutionary terms is ‘language’ in the sense of the highly abstracted and idealized system that typically constitutes the object analyzed in linguistics. Although, indeed, an account of the development of such a system is needed, if the circumstances and manner of utterance production by actual human beings in concrete occasions of interaction is overlooked, important pieces of the puzzle we are trying to understand will almost certainly be missing. Two issues of importance with respect to this are outlined in what follows. […]

Semiotics has to do with texts, that is, with the inscription, transformation and interpretation of organized sets of signs. In this contribution I shall contend that the genealogy of lexicography represents an ideal standpoint to address a central issue for semiotics, namely, how the manipulation of signs and meanings may determine the shaping of cultural objects. I shall begin by introducing the revolution that lexicography undertook during the nineteen century, discussing why this process required the availability of a specific set of concepts, as the one of “meaning” as something mutable and historical, and then how it led up to the emergence of new techniques of the self, to the coming into being of a new kind of people (the professional lexicographer) and to the introduction of new practices of sign-observation and inscription. I shall then consider how the lexicographer, being entitled to select certain definitions instead of others, acquired the power to fix the meaning of terms involving moral and religious content (“marriage”, “conversion”, etc.), to influence scientific and philosophical dispute (defining key-concepts as “continuity”, “belief”, “soul”, “ether”, etc.) and to impact the culture of distant populations by exporting new signs into their language (as the word “God”). Finally, I shall confront the historical development of lexicography with the project of the dictionary of Newspeak that George Orwell described in 1984. […]

Scholars interested in human communication have long recognized that it is necessary to extend the purview of the field of semiotics to include all types of sign-making activity. Barthes (1957/1972: 112), advocating the development of “a semiological science” as earlier suggested by Saussure (1916/1975), drew attention to the diversity and ubiquity of signs: “In a single day, how many really non-signifying fields do we cross? Very few, sometimes none…on the beach, what material for semiology! Flags, slogans, signals, signboards, clothes, suntan even, which are so many messages to me”. It is no surprise then that scholars within the semiotics tradition have attended to the development and proliferation of interactive digital media and software technologies throughout the last century, and the expansion therein of the human capacity for meaningful sign-making activity. This has led to study of multimodality which concerns the often complex interactions of multiple signs, within different semiotic resources such as (spoken and written) language, (static and moving) image, gesture, proxemics, cinematography, sounds, music and displayed art (see Jewitt, 2009; Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006; O’Toole, 1994). […]

Copyright © 2025 | MH Magazine WordPress Theme by MH Themes